So you’re organization wants to get started with UX? Maybe your CMO heard about it at a buzzword-filled session at some marketing conference or as a designer you’re tired of designing, by committee, things that don’t meet user’s needs, or maybe, you’re somewhere in between? Whatever the case, you’ve found yourself at the front lines of advocating for this new approach and all that comes with that. Ok. So do you want the good news or the bad news first?

Bad news…?

Alright. Like me, you like to get that out of the way. Understood.

The bad news is that it’s going to take a lot of time, a lot of passion and a lot of energy. However, you might also find yourself here, because I learned that I liked promoting and talking about UX as much as I liked sitting down with a Brian Eno/Harold Budd record and a hot cup of Kona blend to design (actually, maybe even a little more).

The good news is actually pretty great news.

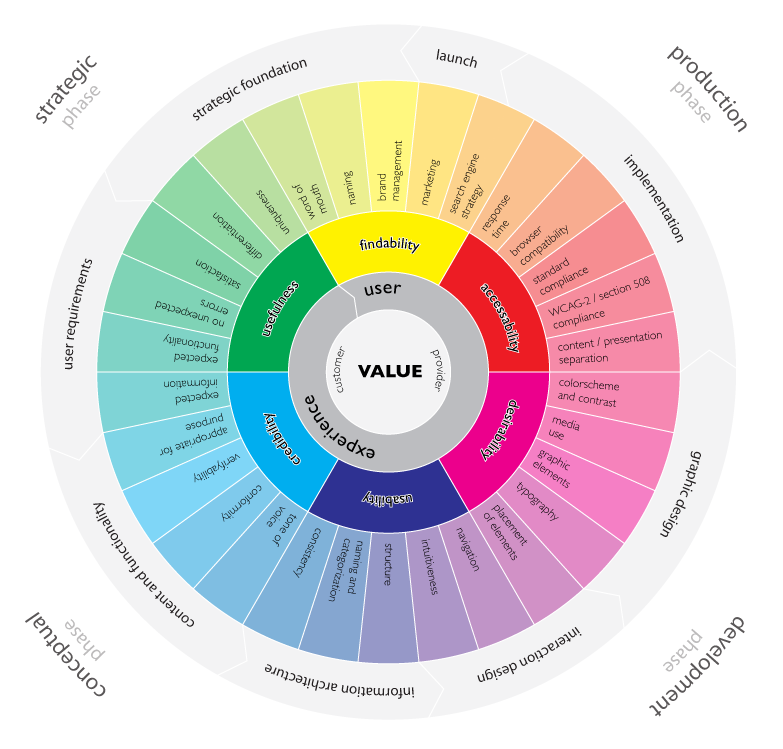

UX has a value proposition that’s pretty hard to argue with, at even the most change-averse organizations.

As with everything, though, there’s a balance. How do you evangelize for the value of UX without overwhelming the organization?

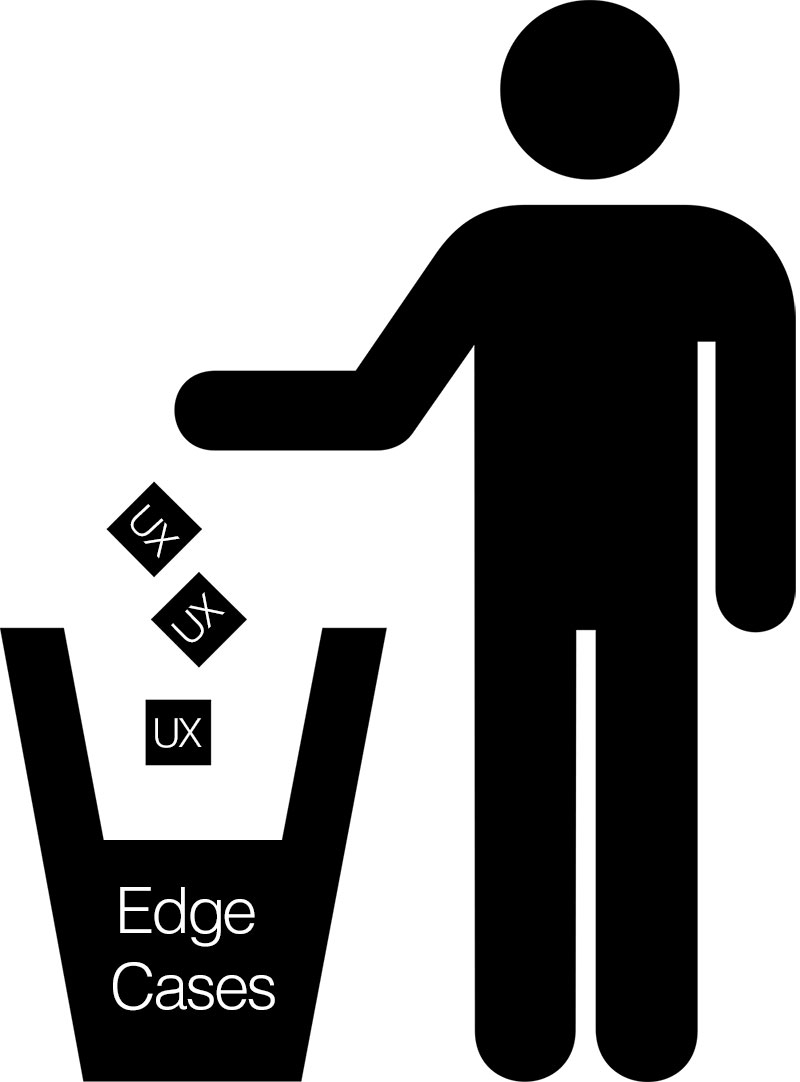

With all of the day-to-day activities it can be hard to introduce new processes, especially if an organization doesn’t think that there are any issues with the current processes and it looks like you’re adding a greater degree of complexity for no apparent value. No worries, but do keep this in mind: Organizations, like people, generally resist change, so like with any kind of change, the less scary you can make something, the better.

The Problem

Before doing anything with UX you have to establish what the problem is. And even though, you, as a designer, are most familiar with the users, and most sympathetic to their needs, and all of your education and experience tells you what the problem is, you have to make the adoption of UX, not about your opinion, or your feelings, but about user problems based on usage data.

Hopefully, you’ve been tracking stuff with Google Analytics, or an occasional survey or maybe some other voice-of-customer feedback tool; if not, no problem, there are a variety of tools you can use to get started. A few examples are: Google Analytics, GoogleDrive surveys, do-it-yourself user interviews, and A/B tests based on paper prototypes. These are quick and dirty ways to begin collecting data on your users, but usually, it doesn’t take a ton of data to begin to see issues, patterns and the areas of discontent for users. Start collecting the data.

Now that you have some usage data it’s time to highlight the issues and to talk about the solution, which is building the UX discipline into your organization.

The Solution

Evangelizing for UX in organizations that already understand it and think it makes a lot of sense are not really the target audience here, so we’re going to focus on the other kind: The organization that doesn’t understand UX and finds any kind of operational change suspect.

Getting an organization interested in UX is a journey of a thousand miles, with each conversation about user data, each shared interaction on user pain and each reference to the concept of ‘user experience’ being a single step. For my mind, the slow-grow approach of evangelizing for UX is the only way, because an organization that goes too fast will get operational whiplash. We don’t want that.

As I stated at the outset, UX creates a value proposition that’s hard to argue with, but people don’t know what they don’t know, and it’s your job to teach them.

With that said, some folks will still try to argue the value of UX. You’ll hear things like “Why would we do this? The users are happy.” Or, “the users don’t care.” Or, perhaps, my favorite “This is the way we’ve always done it, why should we change?” These are not qualitative arguments, these are barely opinions, mostly they’re smokescreens meant to discourage you. Don’t be discouraged. You have your data, you know where the users are struggling and best of all you have a solution to fix it.

The Practice

Often, there’s the question of where one should start with UX and I believe that you should start right where you’re at.

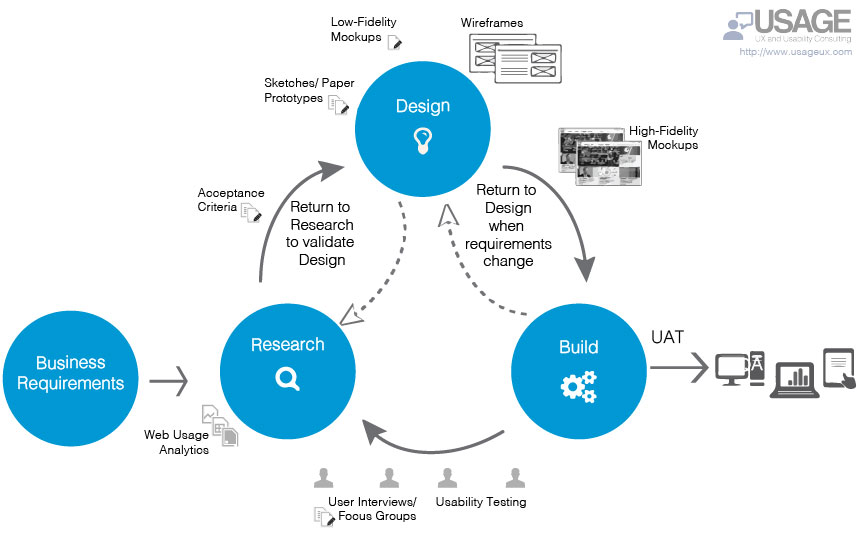

First and foremost, you can talk a lot about UX, but if you can show the results that’s even better… as the saying goes, ‘show, don’t tell.’ Look at ways to integrate paper prototypes into design discussions. Conduct A/B tests internally with fellow employees and organizational leaders. Use low-res mock-ups or wireframes and talk through the interactions. Getting started with UX can be very low-tech and yield incredibly satisfying results, as well as creating positive experiences/stories that will be shared throughout the organization.

At work here, also, is the idea of creating ambassadors for organizational change. I originally heard Eric Quint, Chief Design Officer of 3M talk about this at an O’Reilly Design Conference and it really stuck with me.

The idea is this: The square root of an organization’s employees equals the number of ambassadors needed for organizational transformation. So, if you have 1,000 employees, then you need 31 ambassadors/influencers talking about an idea to effect organizational change. While I never heard of an equation for organizational transformation put just this way, it’s darn accurate in my experience.

The funny thing about the actual practice of UX is that somewhere between getting started, unofficially, just to ‘see how it works’ and full-blown processes being established the discipline of UX takes root. I’m sure it could go the other way, but that’s just never been the case for me. When organizations start to see the positive results of UX and the empathic consideration of a user perspective, it’s as if some area of our lizard brain is triggered, with even those most opposed to the change, getting involved in serving the user. It’s radical and adoption of UX slowly takes hold.

I’m sure there are other, top-down ways to introduce UX. There can be mandates given and directives written, but UX, like any organizational change works best if it happens organically. Whether we’re talking UX or picking a new office supplies vendor, there are varying levels of awareness, acceptance and adoption. In this regard, organizational change works best through gradual repetition and iteration. The worst thing that can happen is that an organization gets overwhelmed by change, UX or otherwise. UX can be a lot of fun, and mostly, folks want to help one another, the user-centered perspective of UX makes it a great practice, not just for making better products, but for bringing people together to solve a common problem.

Takeaways

Do:

- Collect usage data (web analytics, DIY surveys, voice-of-customer feedback)

- Show, don’t tell whenever possible

- Have fun spreading the word of UX with fun exercises

- Create UX ambassadors

Don’t:

- Get frustrated if change doesn’t happen quickly

- Lose sight of your UX goals

- Give up